When Testing Gets in the Way of Teaching: Part 2

Cheat-Proofing Your Assessments

Do you remember writing exams as a student? Or if you are reading this post and you work in education, maybe you have experienced the exhilarating experience known as exam supervision. Either way, I’m willing to bet that the exam room I describe in the next paragraph will sound vaguely familiar.

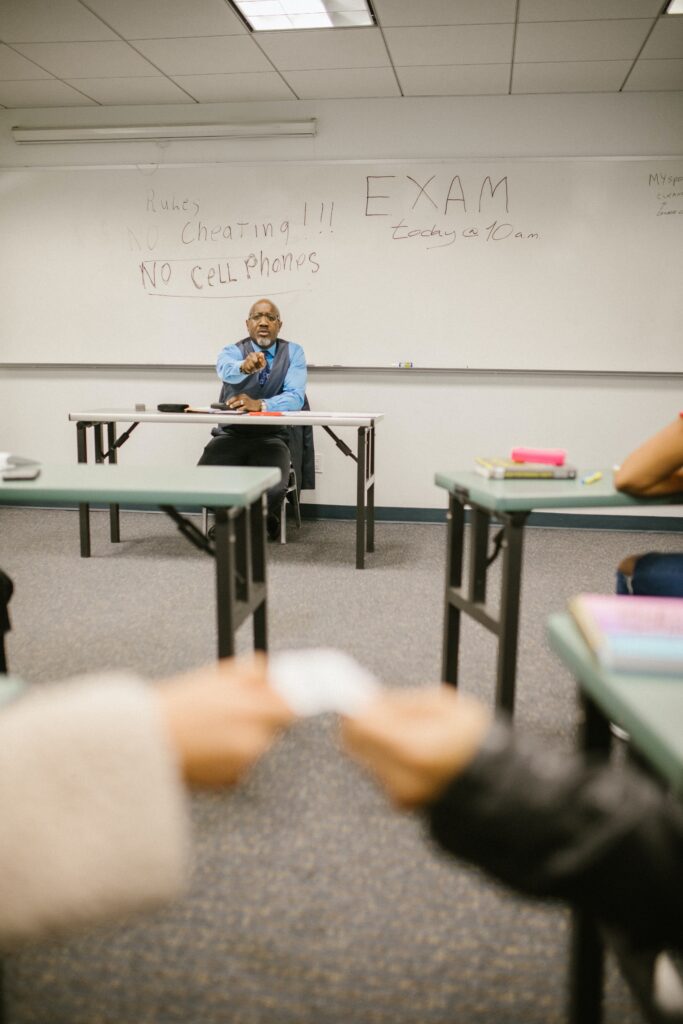

The desks are spaced apart in the school gymnasium. At the appropriate time, students are permitted to enter the room. A teacher greets them at the doorway where they are asked to turn in their textbooks and ensure that their cell phones have been placed in their lockers. Students then proceed to their desks where they take a seat, exams having already been placed upside down on their desktops. At the appointed time, the invigilator announces that the exam has begun and students, in unison, turn over their papers and start writing. Throughout the exam, teachers walk up and down the aisles like prison guards, ensuring that students have their eyes on their own papers. At regular intervals students are reminded of how little time they have left. When the exam is over, students are dismissed one row at a time and exit in silence, unsure of how they just performed.

Why do our exam rooms look like this? It’s certainly not because this environment supports learning. Likewise, there is no research that indicates this is an optimal environment for assessment. The truth is, this environment exists only as a method of discouraging cheating.

Cheating is a topic that has consumed far too much of our valuable time as educators and it is something that we need to leave behind if we want to move education into the 21st century. We need to reimagine how we assess students. We need to design assessment opportunities that are cheat-proof.

What does a cheat-proof assessment look like?

Before we get to that, I want you to consider two questions.

- What is an area in which you excel?

- How do you know that you excel in a particular area?

Take a minute to consider each question before reading on.

All done? Perfect. Let’s look at the first question.

Are you a good gardener? Are you a good carpenter? Maybe you are good at fixing cars, or fly fishing, or playing guitar.

Do you know what all of these skills have in common? You can’t cheat at them. Either you know them, or you don’t. If you enjoy carpentry and you attempt to hang a door, either the door is going to close properly or it won’t. If you plant a garden, either your plants will flourish, or the limited growth you manage will reveal your lack of a green thumb. These tasks are cheat-proof. You can’t fake your way through them. When you attempt them your mastery immediately shines through or your incompetence is exposed.

Teaching and assessment are not separate phenomena. They are deeply connected. They are two different sides of the same coin. We can’t teach in one way and assess in another.

Let’s move to the next question I asked you to consider. How do you know that you excel in a particular area? I’m willing to bet that you do not evaluate your competence in a particular area based on how you once performed on a test. Performing that skill repeatedly with success in real life situations is how you know you are good at what you do. Am I right?

The truth is, you cannot design a paper and pencil test that can measure whether somebody is a good gardener. You can design a test to indicate if they have a broad knowledge of gardening terms, techniques, and plant types; however, doing well on such a test is no indication that a student can actually garden. The only way to get good at gardening is to roll up your sleeves and get your hands full of soil. The learning is in the doing.

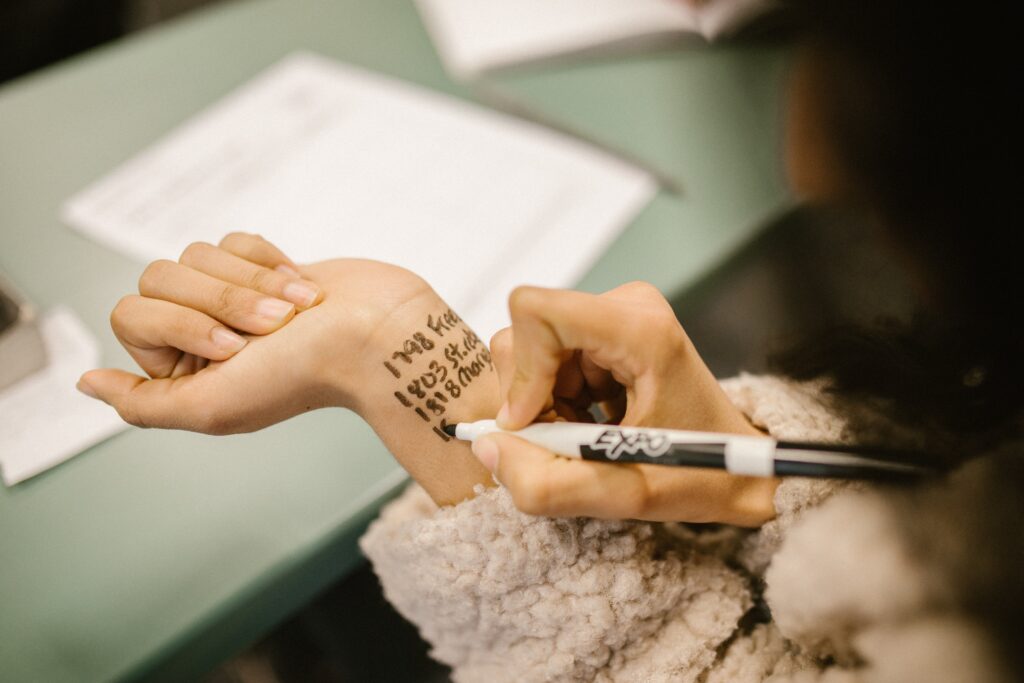

This is how we develop cheat-proof assessments. In order to assess if a student understands something, we need to give them an opportunity to put what they have learned into practice. Students need to demonstrate their learning by “doing,” not by writing tests.

Teaching and assessment are not separate phenomena. They are deeply connected. They are two different sides of the same coin. We can’t teach in one way and assess in another.

Traditionally, schools taught in ways that required rote memorization and recall. You can test in that manner, which is what schools did. But if we are moving towards a model of increased student engagement and authentic learning, we also need to design authentic assessment practices that align with our instruction methods. If the learning is in the doing, it is also in the doing that assessment must happen.

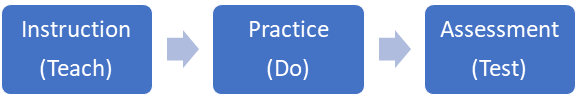

Traditional schooling is designed in such a way where students learn something, they practice this over a short period of time, and then they are given a test on the material they learned. The assessment is totally removed and cut off from the teaching and the practice phases. With no access to notes, books, the internet or their peers, students are ultimately being judged on their memory skills, not their ability to complete a task. Seldom does any learning actually stick with the student. Both teachers and students will tell you that two weeks after a typical test or exam, the student no longer retains what they learned.

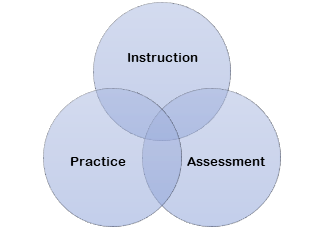

We need to evolve to a model where the instruction, practice and assessment are not three separate steps in a sequence, but rather a web of overlapping connections that are happening simultaneously. We also need assessments to model real life situations. In real life situations, students have access to information and people to help them solve problems. We actually expect that our doctors consult with other doctors and other health care professionals to ensure they are making the correct decisions. Memorizing information is no longer important, but the practical application of that information is where the learning becomes evident.

We cling to paper and pencil tests and high stakes exams because it is what we know. It is what we grew up with. For many of us, it is what we were trained to do. It is also easy.

This conversation around assessment has become more pressing this year due to the COVID – 19 pandemic and the switch to online learning that is happening in many of our classrooms. While I have seen teachers thrive in online environments, many have struggled with how to assess in such a model. When you view assessment as something that lives in exam rooms like the one that is described above, it is hard to reimagine how that has to look in an online environment. Too often, we attempt to create virtual exam rooms like the one above, the teacher now playing the role of a security guard behind a computer monitor, scrutinizing the screen for signs of student infractions.

We need to do better.

Designing authentic learning experiences for all students in our classes can seem like a monumental task. Asking our students how they would like to demonstrate their learning, is a great way to put this work on students. Many students will be eager to take you up on such an offer.

Another simple idea for evaluating students is to have a two minute learning conversation with them, in order to grasp whether or not they know the material. No matter the learning outcome, a two minute conversation will tell you whether they have mastered the material, or whether they are still in the learning stages. No test required. No risk of cheating. No wasted time on test preparation or correcting. It seems like a novel idea, but it’s happening in classrooms already. Even better, it changes the student-teacher relationship and will allow you to get to know your student and their learning style in ways a test never could.

If you are concerned about student cheating, you should be concerned – but about your assessments, not your students. Ask yourself how you would like to be assessed on the skills at which you excel, and make this the impetus for a new cheat-proof method of assessing your students.

Always Be Creating

Always Be Creating  When Testing Gets in the Way of Teaching: Part 1

When Testing Gets in the Way of Teaching: Part 1  Yes, you can be a YouTuber.

Yes, you can be a YouTuber.  The Best Days of Our Lives

The Best Days of Our Lives  Class Dismissed: Lessons from the Last Day of School

Class Dismissed: Lessons from the Last Day of School  When Testing Gets in the Way of Teaching: Part 2

When Testing Gets in the Way of Teaching: Part 2